Infective endocarditis (IE) is a pathology which, despite the progress made in the diagnostic and therapeutic fields, is still burdened today by high mortality and serious complications; therefore, the need for a coordinated approach involving the general practitioner, the cardiologist, the surgeon, the microbiologist, the infectious disease specialist – i.e. the “Endocarditis Team”, and often other specialists: neurologists, neurosurgeons, CHD specialists and more.

Approximately half of patients with IE undergo surgery during their hospitalization and a timely collegial discussion with the surgical team is therefore important in all patients with complicated IE (e.g. endocarditis associated with heart failure [HF], abscess or embolic or neurological complications)

IE can have an acute or rapidly progressive course, but can also present itself in a subacute or chronic form with low-grade fever and non-specific symptoms, but the diagnosis of IE must be suspected in every patient with fever and embolic phenomena or with sepsis or fever of unknown in the presence of cardiac risk factors, such as previous infective endocarditis, valvular heart disease, prosthetic heart valves, venous or arterial catheterization, intravenous electrical devices, congenital heart disease; or patients with non-cardiac risk factors (IV drug use, immunosuppression, dental procedures).

The severity of the clinical picture can be documented by some laboratory tests, such as the degree of leukocytosis/leukopenia, CRP, procalcitonin, ESR and markers of end organ damage (elevated levels of lactate and bilirubin, thrombocytopenia, hypercreatininemia), laboratory parameters also used in scoring systems for the stratification of operative risk in patients with IE, EuroSCORE (European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation). Furthermore, the activation pattern of inflammatory mediators or immune complexes, hypocomplementemia, elevated anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in vasculitis associated with endocarditis.

Imaging methods, especially echocardiography, play a fundamental role both in the diagnosis and treatment of IE both for the prognostic evaluation with IE and for the follow-up during antibiotic therapy.

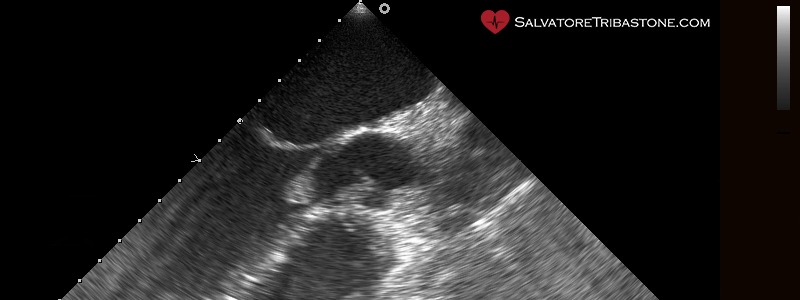

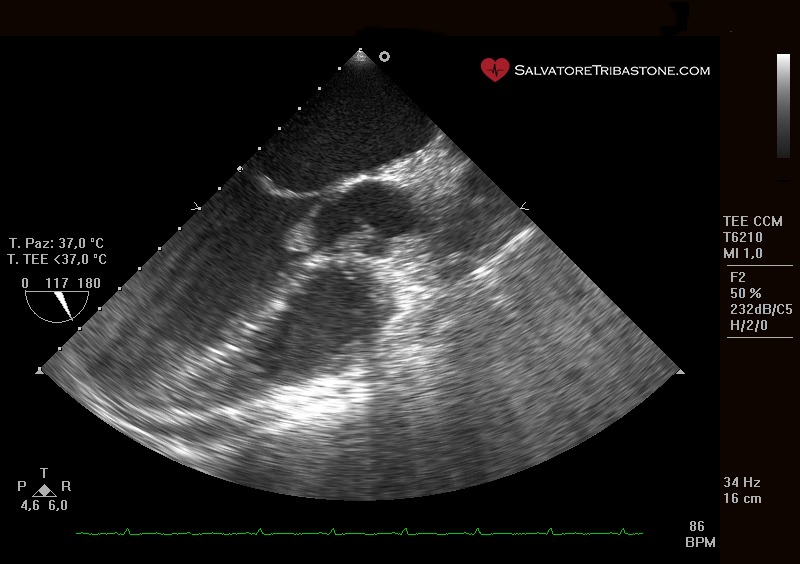

Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) plays an important role before and during surgical treatment (intraoperative echocardiography). However, the evaluation of patients with IE must include other imaging techniques such as MDCT, MRI, positron emission tomography (PET). Finally, SPECT/CT is based on the use of labeled autologous leukocytes (111In-oxime or 99Tc-hexamethylpropyleneamine oxime).

Endocarditic vegetation on native valve – Transesophageal echocardiography

The three echocardiographic findings considered major criteria for the diagnosis of IE are the following: the documentation of vegetations, the presence of abscesses or pseudoaneurysms and the finding of new dehiscence of a prosthetic valve.

The microbiological diagnosis, with positive blood cultures, remains the cornerstone of the diagnosis of IE (at least three sets, containing 10 ml of blood taken 30 minutes apart); blood cultures must necessarily be obtained before administering antibiotic therapy. The constant bacteraemia typical of IE means that there is no reason to wait for the fever peak before taking a blood sample and that all blood cultures are theoretically positive.

If all microbiological tests are negative, the diagnosis of non-infectious endocarditis should be systematically considered and tests for antinuclear antibodies should be performed, as well as for antiphospholipid antibodies (anticardiolipin [immunoglobulin-IgG] antibodies, anti-β2-glycoprotein 1.

In conclusion, echocardiography (ETT and TEE), positive blood cultures and clinical characteristics remain the cornerstone of the diagnosis of IE. The sensitivity of the Duke criteria can be increased using new imaging methods (MRI, CT, PET/CT) which allow the presence of distant embolic complications and cardiac involvement to be diagnosed when the TTE/TEE findings are negative or equivocal. However useful, these criteria cannot however be considered a substitute for the clinical judgment of the Endocarditis Team.

The prognostic evaluation at the time of hospitalization can be performed using simple clinical, microbiological and echocardiographic parameters and must aim to select the most appropriate initial approach. Patients with persistently positive blood cultures after 48-72 hours of antibiotic therapy have a worse prognosis. Patients with HF, periannular complications and/or S. aureus infection show the highest risk of mortality and must necessarily undergo surgery.

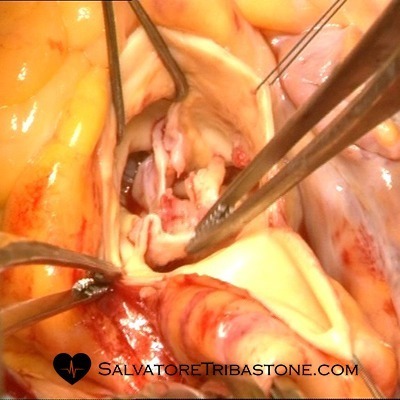

Intraoperative image of Endocarditis on Mitral Valve

Antimicrobial therapy

General Principles: Therapeutic success is based on the eradication of the microorganism using antimicrobial drugs. Surgery can be helpful in removing infected material and draining abscesses; bactericidal regimens have proven to be more effective than bacteriostatic therapy; the association of aminoglycosides with cell wall inhibitors (e.g. beta-lactams and glycopeptides) determines a synergistic bactericidal effect which may allow to reduce the duration of therapy (e.g. oral streptococci) and to eradicate problematic organisms (e.g. Enterococcus spp.).

Slow-growing or dormant bacteria show tolerance to most antimicrobials (except to some extent rifampicin) and are located within vegetations and biofilms (as in the case of PVE), justifying the need for prolonged therapy (6 weeks) for complete sterilization of infected heart valves; the pharmacological treatment of PVE must be of a longer duration (at least 6 weeks) than that foreseen for native valve endocarditis (NVE) (from 2 to 6 weeks), but is substantially similar, with the exception of staphylococcal PVE whose regimen therapeutic treatment must include rifampicin. In patients with NVE who require valve replacement with a prosthesis during antibiotic therapy, the postoperative antibiotic regimen should be that recommended for NVE and not for PVE. In both NVE and PVE, the duration of treatment starts from the first day of effective antibiotic therapy (negative blood culture in the case of an initial positive result) and not from the day of surgery.

Excised mitral valve with endocarditic lesions

Below we list the most common pathogenic bacteria found in IE referring to the guidelines (ESC 2023 and updates) the therapeutic indications:

- Oral Streptococci sensitive to penicillin and Streptococcus gallolitycus group

- Oral streptococci and Streptococcus gallolyticus group resistant to penicillin

- Streptococcus Pneumoniae, beta-hemolytic Streptococcus (A, B, C, and G groups)

- Granulicatella e Abiotrophia (previously known as nutritional variants of streptococci)

- Staphylococcus Aureus and negative-coagulase Staphylococcus. The pathogen most frequently responsible for acute destructive IE is aureus, while CoNS strains are the most common cause of prolonged valve infections (with the exception of S. lugdunensis and in some cases for S. capitis).

- Methicillin- and vancomycin-resistant staphylococci Methicillin-resistant S. aureus strains (MRSA) produce a type 2a penicillin binding protein (PBP2a), characterized by low affinity, from which resistance to most beta-lactams depends. Furthermore, they are generally resistant to a multitude of antibiotics to the point that vancomycin and daptomycin remain the only therapeutic options against severe infections.

- Enterococcus spp.: Enterococcus Faecalis is the most common Enterococcus infection in IE (90% of cases), followed by Enterococcus Faecium (5% of cases). Those bacteria have two major problems: first, they are highly tolerant to the killing effect of antibiotics and their eradication therefore involves the prolonged administration (up to 6 weeks) of combinations with a bactericidal and synergistic action of two cell wall inhibitors (ampicillin and ceftriaxone which act synergistically in inhibiting the complementary PBPs) or a single cell wall inhibitor in combination with aminoglycosides.

- Gram-negative bacteria

- Microorganisms of the HACEK group. Gram-negative bacteria of the HACEK group are unusual microorganisms that require evaluation systems

- IE with negative hemoculture

- Fungi: they are predominantly found in PVE, IE associated with intravenous drug abuse (IVDA) and in immunocompromised patients. Most caused by Candida and Aspergillus spp.

Empiric therapy

Antibiotic therapy for IE must be started promptly, after taking three cultures 30 minutes apart. The initial choice of empirical treatment depends on a series of considerations: whether or not the patient has already received cycles of antibiotic therapy; whether the infection involves a native valve or a prosthesis (and, in the latter case, when the surgery was performed − early vs late PVE); the location of the infection (community-acquired, nosocomial or healthcare-associated IE) and knowledge of local epidemiology, especially in relation to levels of antibiotic resistance.

Recommended therapeutic regimens for the empiric treatment of acute patients: for NVE and late PVE, the antibiotic therapy regimen should be adequate to cover staphylococci, streptococci and enterococci, while that for early PVE or health care must be active against methicillin-resistant staphylococci, enterococci and, possibly, Gram-negative pathogens not belonging to the HACEK group. Once the pathogen has been identified (generally within 24-48 hours), antibiotic therapy must be adapted to the relevant antimicrobial sensitivity profile.

Most common left heart valve complications in IE and how to manage them

About half of patients with IE undergo surgical treatment due to the onset of complications. Surgical intervention is indicated in patients with heart failure (HF) caused by severe aortic or mitral insufficiency, intracardiac fistulas or valve obstruction secondary to the formation of vegetations, as well as in patients with severe acute aortic or mitral insufficiency in the absence of clinical documentation of HF but with echocardiographic signs of elevated left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (early closure of the mitral valve), elevated left atrial pressure or moderate-severe pulmonary hypertension, in both NVE and PVE. Surgery must absolutely be performed as an emergency in those patients who experience persistent pulmonary edema or cardiogenic shock despite medical therapy.

Intraoperative image of Aortic Valve Endocarditis

Indications for Surgery and Surgical Timing in the presence of uncontrolled infection in endocarditis

Persistent infection: In some cases of IE, antibiotic therapy alone is unable to eradicate the infection. Surgery is indicated if, despite an appropriate antibiotic regimen, fever and positive blood cultures persist for several days (>7) or persistent sepsis and after excluding the presence of extracardiac abscesses (splenic, spinal, cerebral or renal) and any other causes of fever.

Signs of locally uncontrolled infection: An increase in the size of vegetations, as well as the formation of abscesses, false aneurysms and fistulas represent signs of locally uncontrolled infection, generally accompanied by persistent fever and for which surgery is recommended in most short time as possible. In summary, uncontrolled infections are mostly related to perivalvular extension and “difficult to treat” microorganisms. In patients with IE, the finding of locally uncontrolled infection constitutes an indication for early surgical treatment.

Hembolics events are very frequent, complicating 20-50% of IE cases, with percentages dropping to 6-21% once antibiotic therapy has started. The brain and spleen are the most frequent sites of embolism in left-sided infective endocarditis, while pulmonary embolism is frequent in right-sided and PM endocarditis. The risk of embolic complications is greatest during the first 2 weeks of antibiotic therapy and is unequivocally related to the size and mobility of the vegetations.

Others complications:

Neurological complications

Infective aneurisms

Splenic complications

Myocarditis or Pericarditis

Heart rhythm and electrical conduction problems

Scheletrical muscles manifestations

Acute kidney insufficiency

© Pietro Di Gregorio for salvatoretribastone.com © ALL RIGHTS RESERVED